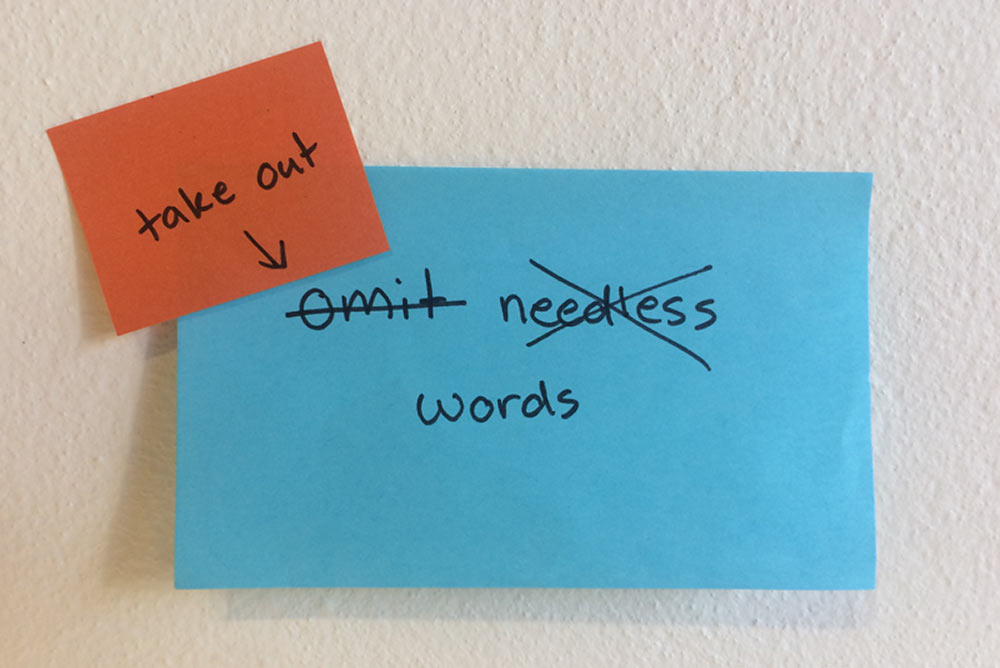

Caption: Post-its on a wall showing edited text.

One of the first things we tell new DTA content designers when they join us is that their words need to be for everyone.

This includes people with languages other than English, people with cognitive challenges, older Australians, people who’ve never had the chance to learn to read well — and everyone else in between.

I recently read an article about a well-known Australian who became homeless for a while. Her ADHD made it too hard to read government information and get the support she needed at the time. It’s stories like this that inspire us to do the hard work to make it simple.

The shorter and plainer the better

For DTA content designers, ‘verify’ becomes ‘check, ‘as a consequence’ becomes ‘because’ and so on.

When 8 words will do the job instead of 18, we use 8.

For example

If there are any points on which you require further explanation or clarification we are available by phone.

Becomes

If you have any questions please call us.

It’s not rocket science but it does take time to craft and polish.

However, what can take even more time (and this also comes up in our content community of practice), are the conversations we need to have with the people who aren’t used to seeing their information presented this way. That is, our colleagues signing off content ‘upstream’ — subject matter experts, business and program leads.

We know there are enormous benefits in keeping online language simple and clear — even when you’re a specialist talking to another specialist. Language that is written as openly and inclusively as possible benefits everyone — not just the 44% of Australians who have a low level of literacy.

It also means meeting the WCAG criteria on reading and comprehension which requires a lower secondary education reading level. Our own Content Guide suggests Year 5 reading level for citizen-facing information.

From my experience, explaining the benefits of simpler writing to colleagues can open the door to more conversation and understanding, and a chance to find middle ground. But to do this, you usually need to ‘bust a few myths’ first.

Myth 1: Experts hate plain English

Experts, and those who have to sign off on specialist advice, battle masses of information on a daily basis. Former UK Minister for Government Policy, Oliver Letwin put it well when he said, ‘there is a tendency [in government] to write a huge amount of terrible guff, at huge, colossal, humongous length’ (The Mandarin).

Unclear, verbose writing frustrates everyone. In one research study (Turk and Kirkman) a group of scientists were presented with both the original and a plain English version of writing. 70% preferred the plainer version saying it was more interesting and stimulating. Over three quarters said it showed more competence and a better organised mind.

Add in quicker reading times and less chance of being misunderstood, and it’s easy to see why highly educated professionals want content that is digestible, concise and scannable (Nielsen Norman Group).

Myth 2: Plain English is ‘dumbing down’

Public servants are a fairly educated bunch and many of us often have to write about complex stuff. This can take a lot of time and late nights.

It’s understandable why people can feel anxious about having their prose changed or worry about having the meaning altered. Avoiding this takes skill and care. According to the Plain English Foundation, when done properly there are enormous benefits to using plain English in business including increased comprehension levels and clearer decision-making.

Reading something and understanding it the first time is a win-win for everyone. More people can understand what you’re trying to say and it’s also easier to translate and find on search engines.

It’s not dumbing down. It’s opening up. Even if people can read the complicated version, do they honestly really want to?

Myth 3: It’s not worth going to the extra effort

Plain language is said to increase perceptions of honesty and trust which is a huge benefit to government, if not a basic obligation to our audiences. There is also enormous social value in making our words more accessible and inclusive.

As for economic value, think about the hours spent rewriting other people’s work to make things clearer. Add to that the extra time you spend rereading things because you can’t understand them. If you work with public information, think about the higher cost of face-to-face and phone transactions versus digital. It all adds up.

Why it is worth the effort

Plain English is not meant to be patronising or overly simple. It’s meant to be helpful and useful in a way that people probably don’t even notice. But it does take a willingness to challenge each other when we spot wording that could be better. A commitment right across an organisation from the top down helps too.

This is an important fight because what is written ‘upstream’ potentially impacts users ‘downstream’ when they try to interact with government online. And most of us don’t interact with government online because we want to. We do it because we need to or have to.

Libby Varcoe is Content Design Lead at the Digital Transformation Agency.

This article was originally published by the Digital Transformation Agency.