If you’re hard-pressed to find a first-rate, recent example of how a well-worn but run-down industrial area can be revitalised into a thriving business precinct, look no further than Emeryville in California.

If you’re hard-pressed to find a first-rate, recent example of how a well-worn but run-down industrial area can be revitalised into a thriving business precinct, look no further than Emeryville in California.

Looking at the area now, which falls within the San Francisco Bay Area in the City of Emeryville in the United States, you’d be forgiven for thinking that it was always a flourishing attraction for some of the world’s trendiest companies.

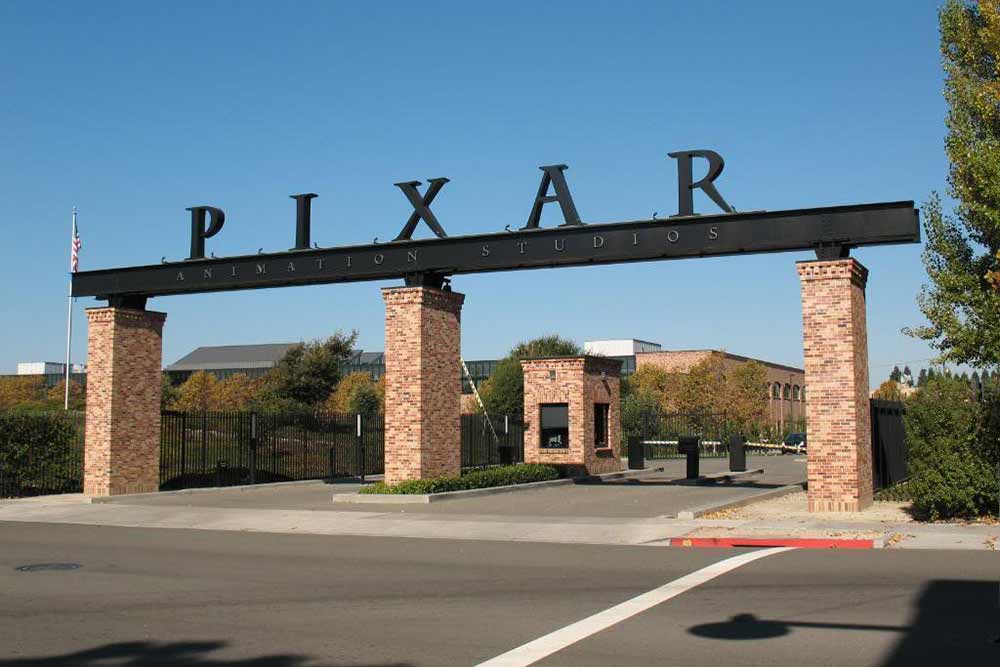

These companies include Pixar Animation Studios, IKEA, Clif Bar, Leapfrog, Peet’s Coffee and Tea, the American Automobile Association of Northern California, Nevada, and Utah, and biotech companies such as Novartis, Grifols Diagnostic Solutions, and Amyris.

The presence of these companies in Emeryville, which is a relatively small jurisdiction of about three square kilometres, makes it a technological and economic epicentre that rivals the nearby Silicon Valley, which itself is home to Adobe, Facebook, Google, HP, eBay, Cisco and Apple, among others.

And of course, the City of Emeryville is proud of its achievements in revitalising the area.

The City’s community development director Charles Bryant, told GovNews about the lengthy process it took to recreate the area, which originated as an industrial hub, with the factories, warehouses, and headquarter offices of many large corporations.

“During this period, only about 2,500 people lived in the city, and railroad spurs ran down almost every street,” Mr Bryant said.

But in the 1960s, as businesses began to abandon their outdated facilities and moved out into outlying areas where land was plentiful and cheap, Emeryville was left to plan how it would fill the void.

What resulted was buildings and former industrial sites wasting away, which created a headache for the City of Emeryville in having to clean up the industrial pollutants that had contaminated the area.

To bring this back in order, Mr Bryant said the council established a ‘Redevelopment Agency’ in 1975, which under state law allowed cities to utilise Tax Increment Funding (TIF) “whereby the increases in property tax that resulted from new development were used to pay for infrastructure improvements and to help catalyse further growth”.

According to Mr Bryant, the strategic use of the Redevelopment tool by the city led to a “complete make-over of the community and a huge increase in both population and employment”.

He said millions of dollars in TIF funding were used to clean up contaminated sites (the vestiges of the previous industrial operations) and to assemble sites for redevelopment.

“The City actively sought qualified developers and worked with them to create office, retail, and residential projects,” Mr Bryant said.

That TIF funding also came in handy in financing the City’s ambitious Capital Improvement Program, including upgraded sewer lines, street beautification projects, and amenities such as parks, bike paths, and community facilities.

The result of this Redevelopment paid in dividends. The population grew from 2,500 to about 12,000 residents and 20,000 jobs in such a small area that’s not that much bigger than Vatican City in Italy.

Now in 2016, the City of Emeryville and its work in reinventing itself as an attraction for technology businesses to survive and thrive has become a benchmark case study for the Future Cities Collaborative, an initiative of the Faculty of Architecture, Design and Planning at the University of Sydney.

Recently the Future Cities Collaborative, led by Professor Edward Blakely, initiated an exchange program that enabled Australian councils to tour sites such as the City of Emeryville, as well as other key locations in the US including Seattle, New York City, Boston and Philadelphia.

One of the key personnel to tour the area was Sydney’s Woollahra City Councillor Katherine O’Regan, who said the City of Emeryville were leaders of their own destiny.

“They developed a plan to make their city a great place and have delivered on it,” Ms O’Regan said.

She said they recognised that they needed an anchor in their city to create jobs and focused on attracting technology companies.

“They also recognised that they could not make a great city on their own so they engaged the private sector to partner and finance projects to grow the city,” she said.

Regarding overseas curiosity in Emeryville’s transformation, Mr Bryant said it’s “gratifying” to know that a tiny city like Emeryville can spark international interest in our story of reinvention.

“It reminds me of the time a few years ago when Emeryville beat out Los Angeles as one of the finalists for the permanent home of the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine, the State’s stem cell research institution,” Mr Bryant said.

He said when he heard the news, the mayor of Los Angeles reportedly exclaimed “Emeryville? Where the hell is Emeryville?”

“That pretty well sums it up,” Mr Bryant said.

This article is one part of our ongoing Shaping The Future series. For an expanded look at our interviews with Ms O’Regan and Mr Bryant, click the link below…

View more from Shaping The Future series See video series and sign up